proposal-optional-types

Introduction

- Authors: @samuelgoto, @dimvar, @gbracha

- Early Reviewers: @adamk, @domenic, @waldemarhorwat, @erights, @slightlyoff, @dherman (mozilla), @avikchaudhuri (flow), @danielrosenwasser (typescript)

This is a stage-0 proposal to add Optional Types to JS and bake them into the open web platform.

For prior art (e.g. other languages, past proposals), alternatives considered (e.g. the status quo, gradual sound typing, decorators and macros), considerations and sequencing we encourage you to start with the FAQ.

In the last 10 years, large engineering teams have developed type systems for JavaScript through a variety of preprocessors, transpilers and code editors to scale large codebases.

Most notably, TypeScript (Microsoft), Flow (Facebook) and the Closure Compiler (Google) have gained a massive amount of adoption and are used as the foundation and starting point of this proposal.

Fortunately, these transpilers share a substantial amount of commonality (syntactically and semantically) and we leverage that as much as we can.

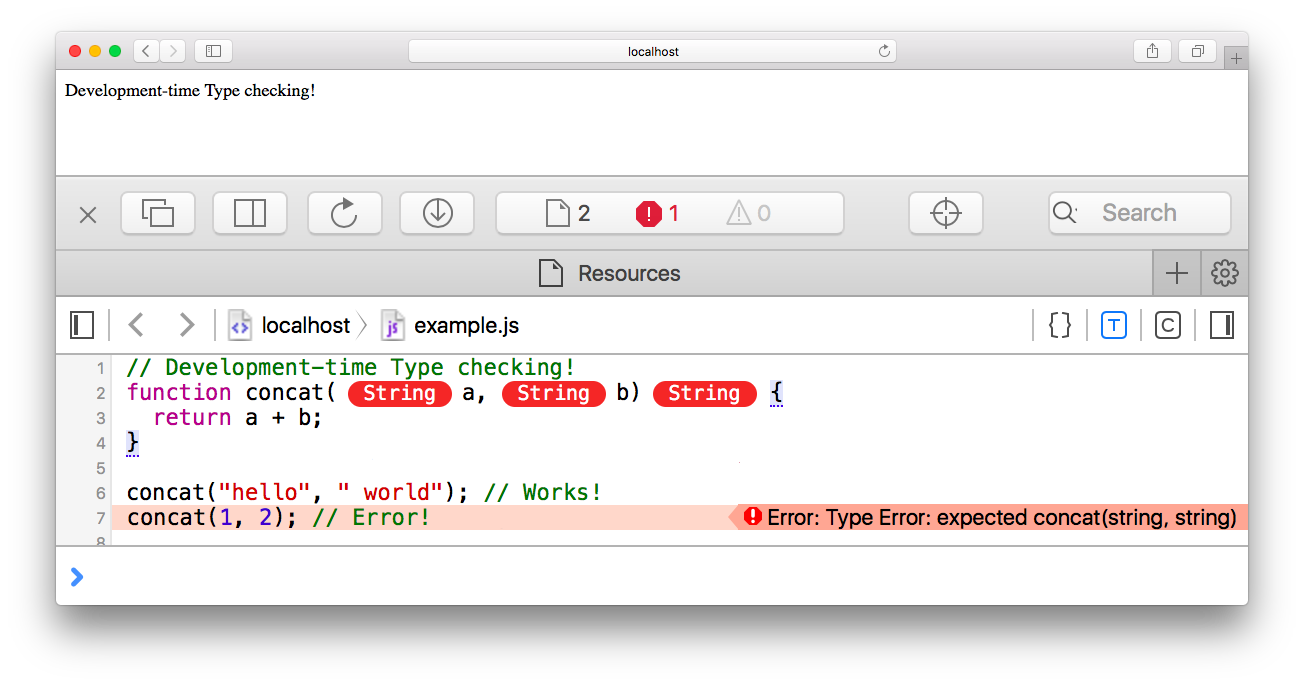

Notably, at the core of these transpilers and hence at the center of this proposal is an Optional Type System: types are used at development-time by type checkers (e.g. on preprocessors, IDEs, code editors, browser developer tools/mode/debuggers, etc) and are erased at production-time by interpreters (e.g. interpretation of javascript for real users in production).

By baking an optional type system into the standard javascript language, we enable browsers to include type checkers in developer tools making type systems (a) more broadly accessible to web developers and (b) more powerful.

An in-browser typechecker works in conjunction with current transpilers who’d have a richer, typed and interoperable (between transpilers) compilation target to use and the added ability to catch type errors at debugging-runtime in addition to errors caught statically (see dart’s checked mode). It also works well in conjunction with minifiers/optimizers which can strip the types prior to deployment or safely assume that they’ll be erased at production-runtime by conformant interpreters.

By making a clear separation between the interpreter and the type checker as separate tools with separate compliance requirements (NOTE(erights) possibly even described in separate docs, viz JSON and i18n), we keep existing javascript programs semantically unchanged (both statically as well as dynamically, e.g. all valid programs remain valid programs, #dontbreaktheweb) while still providing the benefits of type checking.

As a general rule of thumb, at its current stage, this is a proposal for adding “an” optional type system to JavaScript more so than adding “this” specific one. To get the ball rolling, we start with a strawman proposal with some broad strokes (to give an idea of feasibility and desirability), but we are looking to form/identify a working group to collectively define the specifics of the type system at later stages of the process (TC39 members, typescript/closure/flow experts, type system experts, developer tooling experts, etc).

With that, at this stage 0, we are generally looking to:

- Gather early feedback/recommendations/suggestions/validation on the general direction, motivation and approach (e.g. sanity check coverage and trade-offs in FAQ)

- Identify/invite a group of experts interested in the topic (hint: if you are reading this right now chances are you are one of them :)) to form an informal working group.

To kick things off we invite you to take a look at the following strawman and the open design questions section and help us collectively shape what this looks like.

Strawman

To a large extent, like it was said earlier, this is more of a proposal for “a” typesystem (as opposed to “this” typesystem) and a process to get us there.

With this strategy in mind, we are collecting the set of discussion points here (e.g. subset of the minimally-maximal set, sequencing of features, nominal versus structural classes, generics, etc) and as the design choices find convergence we’ll pull them into this section, incrementally making this document converge into our collective choices.

At the core of the existing type systems - and hence of this strawman proposal - is Optional Typing: type checking that is processed at development-time and erased at production-time.

Effectively, most of the information in this proposal is applicable to development-time tools (e.g. code editors, IDEs, compilers and developer tools in browsers). To the extent that new grammar/syntax is introduced and is to be erased - rather than rejected -, the semantics of interpretation of javascript in production-mode remain unchanged.

With that foundation in place, the MVP type system is composed of:

We start by introducing the basic type taxonomy, the typechecking rules, the high level idea of the subtyping rules and we then later give a lot of examples while introducing the syntax.

Type Taxonomy

We could really use some help with the art of sequencing here, but here is our current model for what could form a solid/strong foundation to be built upon.

- The Any type: represents any javascript value

- Primitive types: number, boolean, string and symbol

- The Null and Undefined types

- Built-in Object Types: the built-in standard object types (Object, Function, Error, Array, Iterable, Promise, Number, Math, Date, Map, etc)

- User-defined Object Types: structural types, interfaces, classes, functions arrays

- Union Types: types that represent values that may have one of several distinct representations.

TODO(goto, domenic): A major missing piece is the type definitions for the standard library. We should also say something about the type definitions for the web platform, since that’s JS’s real standard library.

Typechecking Rules

For each expression in the program, we need to define a rule that checks if it is well typed, based on the types of its operands. For example, in a function-call expression, it is a type error if the subexpression in the callee position does not have a function type. For the minus expression, it is a type error if its operands do not have the number type.

For the time being, we do not define the type checking rules in this document. We expect them to be similar to the rules of the existing type systems (TypeScript, Flow, and Closure Compiler). Once there is consensus on the high-level design principles proposed here, we can define the type-checking rules in detail.

Subtyping Rules

The design space for subtyping rules is big, and we have picked some semantics below but we understand they are subject to review and change. With that in mind, here is a strawman proposal:

- The Any type to be a subtype and supertype of all types.

- Classes to be nominally typed.

- Objects types, interfaces and functions to be structurally typed.

- To be safe to use objects with extra properties (Width subtyping) in a position that is annotated with a specific set of properties.

- Function parameters to be contravariant and function return values to be covariant (Type variance).

- NOTE(erights): should methods be covariant (per dart)? TODO(goto): check with @gbracha.

- Arrays to be covariant.

In the next section we’ll introduce the new syntax and with that give a lot of examples on these rules.

Syntax

You associate types with variables using newly introduced syntax:

// Any and Primitive Types

// Variable declarations.

let a: number = 1;

let b: number = 2; // Works!

let c: number = "3"; // Error!

let d: number = NaN; // Works!

let e: number = Infinity; // Works!

// TODO(goto): craft really good examples for Any

Functions are extended to type parameters and return values:

// Functions

function concat(a: string, b: string): string {

return a + b;

}

concat("foo", "bar"); // Works!

concat(true, false); // Error!

let c: number = concat("foo", "bar"); // Error!

// TODO(goto): come up with a better example.

It is safe to substitute a function that accepts a more general argument (contravariant inputs) and returns a more specific value (covariant outputs).

// Function subtyping

function fetch(

url: string,

callback: (result: string) => number | undefined) {

// ...

}

function a(result: string | undefined) : number | undefined {}

function b(result: string) : number {}

function c(result: boolean) : number | undefined {}

function d(result: string) : number | undefined | null {}

fetch(“data.json”, a); // Works

fetch(“data.json”, b); // Works

fetch(“data.json”, c); // Error

fetch(“data.json”, d); // Error

| With Union Types you can represent types that can have one of several distinct representations. A value of union type of A | B is a value that is either of type A or type B. |

// Union Types

let x: string | number;

let test: boolean = true;

x = "hello"; // Ok

x = 42; // Ok

x = test; // Error, boolean not assignable

x = test ? 5 : "five"; // Ok

x = test ? 0 : false; // Error, number | boolean not assignable

Types are non-nullable by default, and types can be made nullable by using explicitly the union type. Function parameters and object properties are required by default and can be made optional by using union with undefined.

// Optional and Nullable Types

function a(value: number | undefined | null) {

// …

}

a(42); // Works!

a(); // Works!

a(undefined); // Works!

a(null); // Works!

a("42"); // Error!

Object literals give you the ability to create structural types:

// Object Literals

// object type literals give you the ability to add types to objects!

var person: {

firstName: string,

lastName: string,

age: number | undefined

} = {

firstName: "Sam",

lastName: "Goto",

// age is optional! phew!

};

Interfaces provide the ability to name structural types. Interfaces have no run-time representation and are purely a compile-time construct. Class syntax is extended so that classes can declare the interfaces they implement.

// Examples

interface Bar {

hello(a: number): number;

}

class Foo implements Bar {

bar(a: number) : number {

return 0;

}

}

// TODO(goto): find a better example here.

To create an Array type you can use Array

// Examples of Array Type Usage

(example from flow’s array types and typescript’s)

let arr1: Array<boolean> = [true, false, true];

let arr2: Array<string> = ["A", "B", "C"];

let arr3: Array<any> = [1, “two”, false];

let arr4: Array<number|string> = [1, 2, 3];

let a: string[] = ["hello", "world"];

// Arrays are covariants.

let arr5: Array<any> = arr1; // Works

let arr6: Array<string> = arr4; // Fails

arr4 = arr2; // Works

// Since the 10th element isn’t set, this returns undefined at

// runtime. The type system assumes bounded access though, allowing

// val to be of type string rather than string | undefined.

let val: string = arr2[10]; // Works

Note that this notation is a special case of of generics, so things like Array<? extends Type> aren’t yet allowed until generics are introduced (see section on Future Work in the FAQ).